It is wonderful that nearly everyone today agrees that the natural environment needs caring for. Ever since the first astronauts sent back images of our green blue planet surrounded by the darkness of space the awareness has grown that we can do harm as well as good to the planet.

However disagreements creep in when we consider which actions most benefit the natural world. And because so many of us care so passionately about the issues, I will argue this is the clearest example of where our emotional, subjective thinking has predominated at the expense of our cooler, objective thinking.

Consider these five popular environmental aims:

- Reducing the quantity of plastics in rivers and oceans

- Preserving habitats where endangered species live

- Reducing the amount of air pollution, especially nitrous oxides and particles from burning coal and diesel

- Restoring habitats damaged by pollution, mining, industrialisation or poor farming techniques

- Stopping the climate from changing

Four of these five aims are comparatively straightforward: ‘SMART’ targets can be set and progress towards achieving them can easily be measured.

Laws can be passed to make it illegal to dump plastics in rivers and oceans: alternative waste treatment sites can be established, and measures taken to remove plastics already in rivers and oceans.

Coal and diesel can be replaced by cleaner fuels, or filters applied to power stations.

Habitats can be protected and restored through replanting appropriate plants and reintroducing endangered animals.

The effectiveness of all these policies can be measured, and changes made if needed. The cost of each can be weighed against other priorities. In other words, ordinary objective thinking can be easily applied.

The fifth aim, stopping the climate from changing (usually phrased ‘stopping climate change’) is different in kind from the other four. The issues involved are vastly more complicated and as it is a global issue it is currently impossible to measure if the actions being taken are having the desired effect or not. Let us look at some of the difficulties.

We can be pretty sure that the climate has always changed. 12 000 years ago, this place in Somerset where I’m writing this book was under about 100 feet of glacial ice. 50 000 years ago there was a tropical climate here.

You can see the fossilized bones of lions, hippos and elephants in the Museum of Somerset in Taunton. After that, woolly mammoths roamed the land. There is no evidence that the climate has ever been static, so stopping all future changes may not be possible.

Furthermore, there is the complexity of separating climate from weather. At any time in the world some people are coping with 40°C heat while others struggle with -40°C cold. Over the course of every 24 hours most people experience a temperature range of at least 10°C, and a range of 20-30°C is not uncommon.

Often when it is hotter or colder than usual it is not that the overall climate has changed but that we are getting ‘someone else’s weather’. Changes in the direction of the gulf stream can bring either winds from the warmer south or the colder north (this is of course from a UK point of view).

It is incredibly difficult to abstract an average global temperature. Vast amounts of data are required and huge computing power. This has begun to be possible in the past decade or two. The problem is, such accurate measuring cannot be backdated into the past: the first humans only reached the north and south poles in 1909 and 1911 respectively.

Instead, climate scientists make deductions from other evidence such as gases trapped in ice cores and the thickness of tree rings.

However there are broad areas of agreement. Most agree that the overall climate today is warmer than during the last Ice Age, ending about 10 000 years ago. More recently, there was a medieval warm period (when the Vikings grew barley and trees on Greenland, both impossible today).

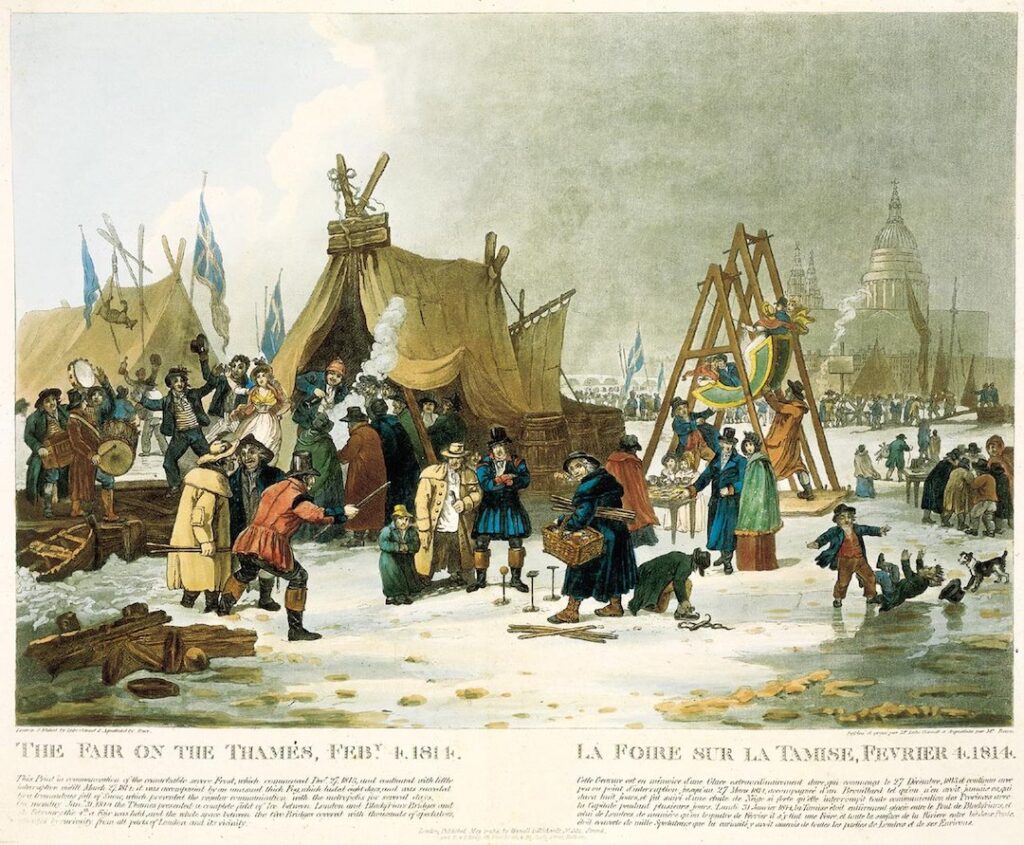

Later there was a ‘Little Ice Age’ from the 17C to the early 19C. In the UK this meant that winter ‘frost fairs’ were frequently held on the frozen solid river Thames in London (the last one was in 1814).

It is hard to abstract an average global temperature but it seems likely that we’ve been on a gently warming trend since the last Ice Age, and more specifically on a warming trend since the end of the ‘Little Ice Age’ in the early 19C.

This has coincided with the Industrial Revolution and an increase in Carbon Dioxide gas into the atmosphere from approximately 280 ppm (parts per million) to 400 ppm today.

Correlation can reveal causation and many climate scientists today argue that the CO2 released into the atmosphere from human activities has become the main driver of climate change. Many argue that if the rate of CO2 emissions remains on current trajectories the resulting global warming could be catastrophic.

Other climate scientists, it is worth noting, argue that CO2 is only a trace gas and has little impact compared with other greenhouse gases, in particular the 100x more abundant water vapour. They argue that other factors have a much greater impact on the climate including subtle changes in the earth’s orbit through space around the sun and changes in sunspot radiation.

Edward and Annie Maunder pointed out that the start of the ‘Little Ice Age’ corresponded with a time of minimal sunspot activity, between 1645 and 1715, giving rise to the term ‘maunder minimum’ for such periods. Some climate scientists predict a new maunder minimum very soon, and that the current warming trend will be replaced with a cooling one.