What do the terms ‘left wing’ and ‘right wing’ actually mean, and where did they come from? The answer is surprising.

In theory, we get to choose what kind of government we have. In practice, it seems the really important decisions are kept out of reach. Our democratic votes can change the crew running the ship but seem to have little effect on its overall direction.

It is worth considering how did we get here, and what would need to change to bring the decisions that really matter back on to the ballot slip.

In many countries there is no chance to choose who rules. In many others, corruption is so widespread that there is little faith that politicians will do anything that benefits anyone other than themselves. In some African countries they are called the ‘wabenzi’ – the people who travel in chauffeur driven Mercedes Benz cars.

Even in so called mature Western Democracies there is widespread disillusionment with the choices we face. Governments often do the opposite to what they say they will do when asking for votes. They always promise that things will get better, when in reality they often get worse. Voting often seems to be having to choose the least bad option.

Like sports teams, political parties have team colours and aim to arouse strong emotions in their supporters. If they are lucky, this support will be passed down from generation to generation. The team with most support gets the prestige of office and the chance to direct how billions and billions of pounds, dollars or euros are spent.

Successful politicians appeal directly to voters’ subjective, emotional thinking. They may have such hard to pin down qualities as charm, charisma, physical attractiveness, a sense of reassurance, a sense that they understand what you are going through, and that above all they have your best interests at heart.

Yet what matters most is what politicians actually do. Do their decisions make life better or worse? Is it possible to bring objective thinking to bear on the alternatives we are presented with?

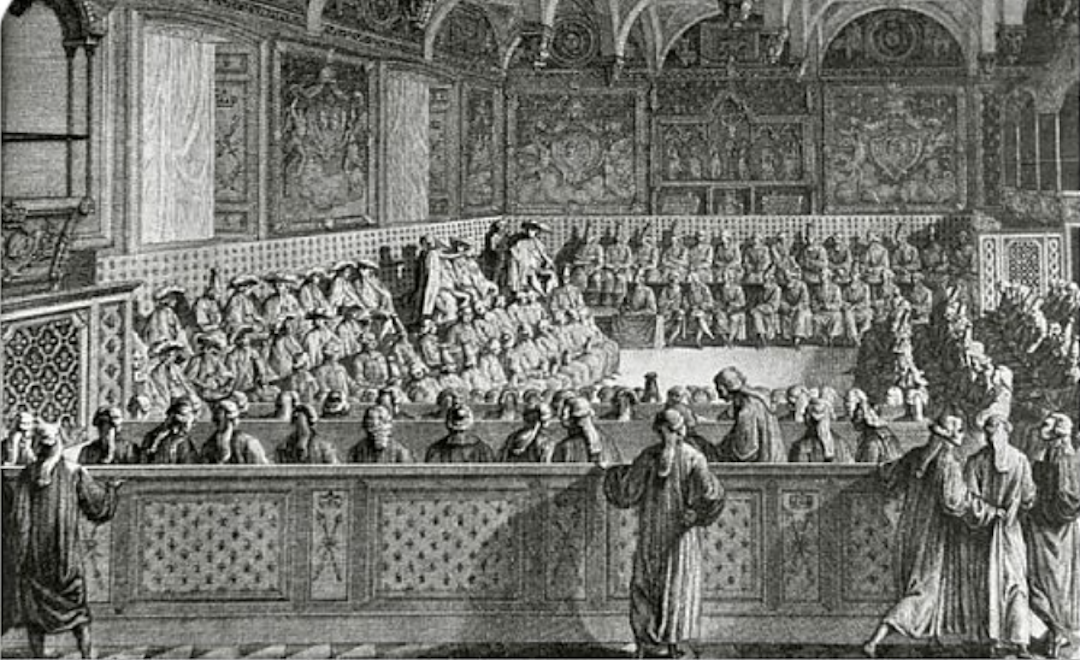

In the 19C French parliament, supporters of the status quo sat on the right hand side as you entered, and those wanting change sat on the left hand side. From this accident of history arose the concepts of “right wing” and “left wing”.

Generally, in the 19C to be right wing meant you supported the big landowners and industry owners, and traditional institutions like the monarchy (UK) and the established church. You were “conservative” – you wanted to keep the good that had been handed down.

In contrast, the left wing wanted change. They wanted to limit the size and power of all the ‘vested interests’: the large landowners and business owners and even the state itself.

They sought to open up opportunities and break down barriers to entry for people starting new businesses. Economically they were largely “Liberal”, believing strongly in freedom and allowing individual opportunity.

The late 19C and the 20C saw the dramatic rise of socialism. Socialists also wanted to restrict the power of the traditional vested interests but saw the main way of achieving this being through increasing the powers of the state, accompanied by the restriction or even abolition of private property.

Socialists also sat on the left hand side, and as they grew in numbers and influence the term ‘left wing’ changed in its meaning.

Today “left wing” is usually taken to mean socialist and ‘centre left’ to mean social democrat. “Right wing” can mean traditional conservative, or a militaristic nationalist.

Generally, the left wants a large state and lots of welfare: the right wants a large state and more military and national pride.

Classical Liberals, who generally favour a smaller state, do not fit on this line: they used to be seen as on the left, but now are usually grouped with the right even though they are instinctively internationalist and opposed to militarism.

When presented with a left-right axis most people go instinctively somewhere near the middle. People don’t like to be thought of as ‘extreme’. Hence the flourishing of the so-called ‘centre ground’. This is more accurately described as some kind of ‘social democracy’ – a very large state by historical standards (approx 40-60% of GDP) but falling short of full socialism.

Astute politicians use regular polling to determine what is currently popular and shamelessly ‘steal’ their opponents’ most popular policies, making it hard to plot the different parties on the old left-right axis.

To put this in UK terms, is it really easy to say who is more ‘left’ or ‘right’ wing out of Tony Blair, Gordon Brown, David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson?

Where delegates sat on a 19C seating plan does not map very well onto the main choices we face in a 21C democracy. Is there an alternative that has actual descriptive power? In other words, is there an objective way of mapping political parties based on something measurable?